Bette Smith>Mildred Cameron>Stella Knox>Wm Wallace Knox>Margaret Anderson>Ann Graves> Richard Darling Graves>Mary Wragg>her brother William Wragg (my sixth great uncle)

Those concerned in our story as it begins in Montreal 1819

The Graves

- Richard Graves, out-of-work Master Blacksmith, lately returned from New York City

- Juliann Maville [Richard’s wife] and four of their six children[ii]:

- Richard Graves, Jr., aged 14 years

- John Darling Graves, aged 12 years

- Juliann Graves, aged 9 years

- Ann “Nancy” Graves, aged 6 years

- Juliann Maville [Richard’s wife] and four of their six children[ii]:

- Ann Graves, living on DeLaGauchetière Street near St-Urbain, Montreal [Richard’s sister]

- Isaac Shay, a builder and co-owner of Shay & Bent Co. [Ann’s husband]

The Wraggs[iii]

- Ann Wragg, Widow John Platt, living at Sherbrooke Street, Montreal [Richard’s aunt]

- Elizabeth Mittleberger, Widow George Platt, living at 70 St-Paul Street, as well as Sherbrooke Street, Montreal [Ann Wragg’s daughter-in-law]

- Benjamin Wragg, Master Blacksmith, living at 109 Notre-Dame Street, Montreal [Richard’s uncle]

- Marie-Josephe Roi [Benjamin’s wife]

- Elizabeth Wragg, living at 15 Ste-Maries Street, Montreal [Richard’s aunt]

- Richard Porteous, Tavern Keeper and Distiller [Elizabeth’s husband]

- William Wragg, Master Blacksmith, living at 12 St-Paul Street, Montreal [Richard’s uncle]

- Sophia Low [William’s wife]

Richard Graves, his wife Juliann Maville and his children had returned to Montreal by August 1819. All was not well. Richard was suffering from a debilitating medical condition which made it impossible for him to carry on his trade as a blacksmith. He had declared bankruptcy in New York City just two years previously and likely had very little money or property. Bluntly put, he could not provide for his family.

He and his wife made the hard decision to place three of their children as apprentices with Richard’s uncles, William Wragg and Richard Porteous. The agreements were drawn up by Richard with his uncles, but approved by Juliann who made her mark on each contract. While the oldest son, Richard Jr., was apprenticed to William Wragg as a blacksmith, the two girls were apprenticed “to serve” their masters, no doubt as domestic servants. Juliann was apprenticed to Richard Porteous, tavern keeper, and Nancy to William Wragg, master blacksmith.

Apprenticeship Contracts

I will begin with Richard Graves, Jr., but first I should note that his father and his uncle, John Graves, were themselves apprenticed at approximately the same age to their grandfather Richard Wragg, a Master Blacksmith. This gives weight to the idea that Richard and Juliann felt the extended Wragg family to be the best choice to care for their children. With respect to William Wragg, Richard Darling Graves’s brother John had been a witness at William’s marriage to Sophia Low, while Richard Porteous had been a witness to Richard and Juliann’s marriage. Family ties were strong.

Richard Jr.’s apprenticeship contract[v] is fairly standard and binds fourteen-year old Richard to serve as an apprentice “in the said Art and Trade of a Blacksmith until he shall have attained & completed the full age of Twenty one years”. Richard agrees to serve faithfully while William Wragg agrees he “shall and will teach and instruct or will and sufficiently cause to be taught and instructed in the said art and trade of a Blacksmith and everything thereunto belonging after the best way and manner that he can…and will find and allow unto his said Apprentice: Meat, Drink, Washing, Lodging and Wearing Apparel both Linen & Woollen. And all other necessaries both in Sickness & in health as is meet and convenient for such an apprentice during the said term.”

It is in Richard Jr.’s contract that we are told why Richard and Juliann took the decision to give up their children. The following clause was inserted:

…nevertheless should the said Richard Graves the Father recover from his present illness and commence business again as a Blacksmith it shall and may be optional with him to take back his Son to assist him in his said capacity as a Blacksmith in which case this agreement to be null & void —

Juliann (aged nine years)[vi] and Nancy (aged six years)[vii] had contracts similar to Richard Jr., but their contracts ended when they were eighteen years of age. Standard contract restrictions for the two girls which were not applied to Richard Jr were:

She shall not haunt or frequent Playhouses, Taverns or Ale houses. She shall not contract matrimony. She shall not at any time day or night depart or absent from the said service without leave.

It seems odd to me that the restriction concerning Taverns or Ale houses was included in Juliann’s contract because she was apprenticed to a Tavern Keeper. It may be that Richard and Juliann expected that she would serve in Richard Porteous’s family home and not his business or, then again, this may simply be standard wording for contracts for domestic servants.

Also included in the girls’ contracts was the following wording regarding the care to be given the children by their masters: “And also that they shall and will well and humanely treat her Instruct her or cause her to be instructed in all necessary Housework in they [sic] best way and manner that they can.”

This idea of child labour sounds harsh to our 21st century ears. However, training a young girl to be a servant was also a way to prepare her to run her own household following marriage. Claudette Lacelle in her article “Domestic Servants in 19th Century Canada” writes that few households in Montreal and Quebec City would have employed servants and in about 60% of the cases, only one live-in maid-of-all work was hired, although this did not preclude hiring outside domestic help.[viii] It is most likely that Juliann and Nancy would have been trained, either by their great aunts, Elizabeth Wragg and Sophia Low, or by another domestic servant within the household. Lacelle goes on to discuss the advantages of domestic service.

When one considers the multitude of tasks awaiting a servant, the constant attendance demanded, and the insecurity inherent in the position as well as the loneliness the majority most likely experienced and the little liberty they enjoyed, one can wonder why they would hire out as servants, or alternatively, put their own children into service. Advantages had to outweigh disadvantages.

One advantage was that domestic service represented a type of social assistance or security. At the beginning of the 19th century, poverty was the lot of many. Indeed, it was not unusual to read in the newspapers of a family found dead from hunger and cold in the hovel that was their home. It is therefore easy to understand why being in service was desirable: board, lodging, and upkeep were assured. More than one child’s contract, in fact, states that the family could not provide for his or her needs, especially when the mother was alone. Sending a child into domestic service meant sending it into security and ensuring its survival….

…Finally, it is also very likely that life was changed and improved in many families because of the large number of women who learned how to tend house while in service. Becoming a domestic servant, therefore, could also have been perceived as a good apprenticeship for the future. We will never know whether entering service was a matter of choice or necessity for the majority, but the fact remains that some must have benefited from the advantages it offered at that time.[ix]

Claudette Lacelle, “Domestic Servants in 19th-Century Canada”, pp. 39-40

Lacelle provides an extract from a 19th century manual which would have applied to a “maid-of-all-work” circa 1860:

The maid must be up by six o’clock, do her hair, ready herself and only go down to her kitchen when ready to go out to the market. Between six and nine o’clock, she has time to do many things. She will light the range and fires or stoke the stove. She will prepare the breakfasts, tidy the dining room, brush clothes and clean shoes. Here, the masters rise early; she shall do the rooms, put water in the washbasins, bring up wood or coal and take down rubbish. For all these duties she must wear sleeve protectors and a blue apron. She will do the market, if Madame does not go with her, and will not linger to talk; her time is precious. She will set the table, prepare luncheon, put on a white apron for serving and will be careful to wash her hands. Then, once the dining room has been tidied, the dishes washed and put away, the kitchen utensils cleaned, she may, before preparing dinner, carry out a special task for each day of the week. For instance, on Saturday thoroughly clean the kitchen and equipment; Monday the lounge and dining room; Tuesday, the brass in the bedrooms; Wednesday, washing; Thursday, ironing….[xi]

Lacelle, Ibid., Appendix E, p. 156.

As children, neither Juliann nor Nancy would be expected to do everything that an adult servant would perform. However, they likely did start their day very early, likely around 5:30 am and went to bed late at night, with many tasks and lessons to fill their waking hours.

Little Juliann, who was apprenticed to Richard Porteous, died in Montreal on November 26, 1821 at the age of eleven and was buried two days later in the Wragg burial plot at the St-Lawrence Protestant Cemetery. This cemetery was located on what was then Dorchester Street, now René Levèsque Boulevard West. The burial register lists Juliann as Richard Porteous’s servant.[xii] There is no notation that her remains were exhumed and conveyed to the new Mount Royal Cemetery when the St-Lawrence Cemetery was closed. Much of the old cemetery lies beneath Complexe Guy Favreau, a federal building at the corner of St. Urbain Street that went up in the mid-1980s. Workmen encountered many burials during construction which were then moved to Mount Royal, but most burials remain in the Old Cemetery and some burials are still being discovered when roadwork is done on René Levèsque Boulevard.[xiii]

John Darling Graves had initially gone with his father to Quebec City where, at the age of fourteen, he was apprenticed for a short while to the Hon. Charles William Grant, a member of the Legislative Council. John had been apprenticed to learn the “art, trade and business” of an Engineer “attending and conducting a Steam Engine.” As part of the 1822 contract[xiv], Grant was to provide for John’s education in reading, writing and arithmetic. Unfortunately, this apprenticeship does not appear to have been successful. John was likely in Montreal when his father drew up a Power of Attorney[xv] on November 21, 1823 giving his brother-in-law Isaac Shay authorization to “take charge and care” of John who was now sixteen years old. Shay was given carte blanche to “cause him the said minor to regularly to [sic] learn such trade and business as the said Isaac Shay shall think and judge him more apt and fitte[d].” John’s mother, Juliann Maville, did not co-sign the 1822 contract and was not mentioned in the 1823 Power of Attorney. I have not been able to find any further apprenticeship contract for John. If he apprenticed with Isaac Shay he would have lived on DeLaGauchetière Street with his Uncle Isaac and Aunt Ann. At this point John disappeared from our family’s history and I have been unable to trace him further.

In 1825, the William Wragg household was enumerated in the census of Lower Canada.[xvi] Only the name of the head of the household was given. William’s household was comprised of seven people. Of these, 2 were girls under fourteen years [Nancy Graves and an unknown child][xvii], 2 were men between the ages of 18 and 25 [Richard Graves Jr. and Benjamin Wragg Jr.], 1 was an unmarried woman between 14 and 45 years [unknown person, possibly a domestic servant], 1 was a married woman between 14 and 45 years [Sophia Low], and 1 was a married man between 40 and 60 years [William Wragg].

Benjamin Wragg, Jr. was the son of Benjamin Wragg, Master Blacksmith. When his father died in May 1821, his step-mother, Marie-Josephe Roi, arranged for sixteen-year-old Benjamin to be apprenticed to her brother-in-law William Wragg as a Farrier. There were, however, specific clauses and corrections that were made to Benjamin’s contract:

Wm. Wragg promises to provide good and wholesome board, lodging, clothing and other necessarys fitting for an apprentice, to teach or cause to be taught Benjamin the art and trade of a

blacksmithfarrier as far as in his power, should Benjamin at any time within the period mentioned wish to join any other trade that than of ablacksmithfarrier that William Wragg willbe at libertybind him to such trade chosen by Benjamin when a suitable and proper Master shall be found to instruct him, to procure immediately 3 months day schooling and afterwards 3 months night schooling each winter provided he remains with him.[xviii]

This contract did not last and was voided by mutual consent in July 1826. Further research has shown that Benjamin became a stone cutter[xix] and mason who then immigrated to New York State.

An Accident Occurs

In 1824 William Wragg had a serious accident which prevented him from working as a blacksmith.

Montreal July 31 – Accident. In the evening of the 23 of this month [July 1824], as Mr and Mrs William Wragg were taking the air in a calèche [horse-drawn carriage], the horse stumbled at the entrance of the Faubourg St. Antoine, and the shock of the carriage threw Mr Wragg out, who fell on the side of his head and his right shoulder. He broke a bone in his neck and dislocated his shoulder. A crowd gathered, frightening the horse, which carried Mrs Wragg at a gallop over a bridge. She was in an alarming situation for a considerable time, but only got herself out of it by her courage and presence of spirit.[xx]

Le Canadien, Quebec City, 4 Aug 1824, p. 1. [Translation from the original French by Margaret Goldik, 25 Jun 2022]

William took on a partner in 1825 but he needed three years to fully recover and when he did, he took out an advertisement on October 31, 1827 to announce the fact.

Notice—The Subscriber, grateful for the liberal encouragement which he has experienced from the public, announces that he has resumed the business of BLACKSMITH, which owing to ill health he has not been able personally to pay attention to for these past few years past [sic] – Those who favor him with their custom may rest assured of his attention to execute all work with fidelity and dispatch, at his old stand, No 12 St Paul Street….William Wragg, Montreal, 31st Oct., 1827. [xxi]

The Montreal Herald, 13 Feb 1828, p. 2.

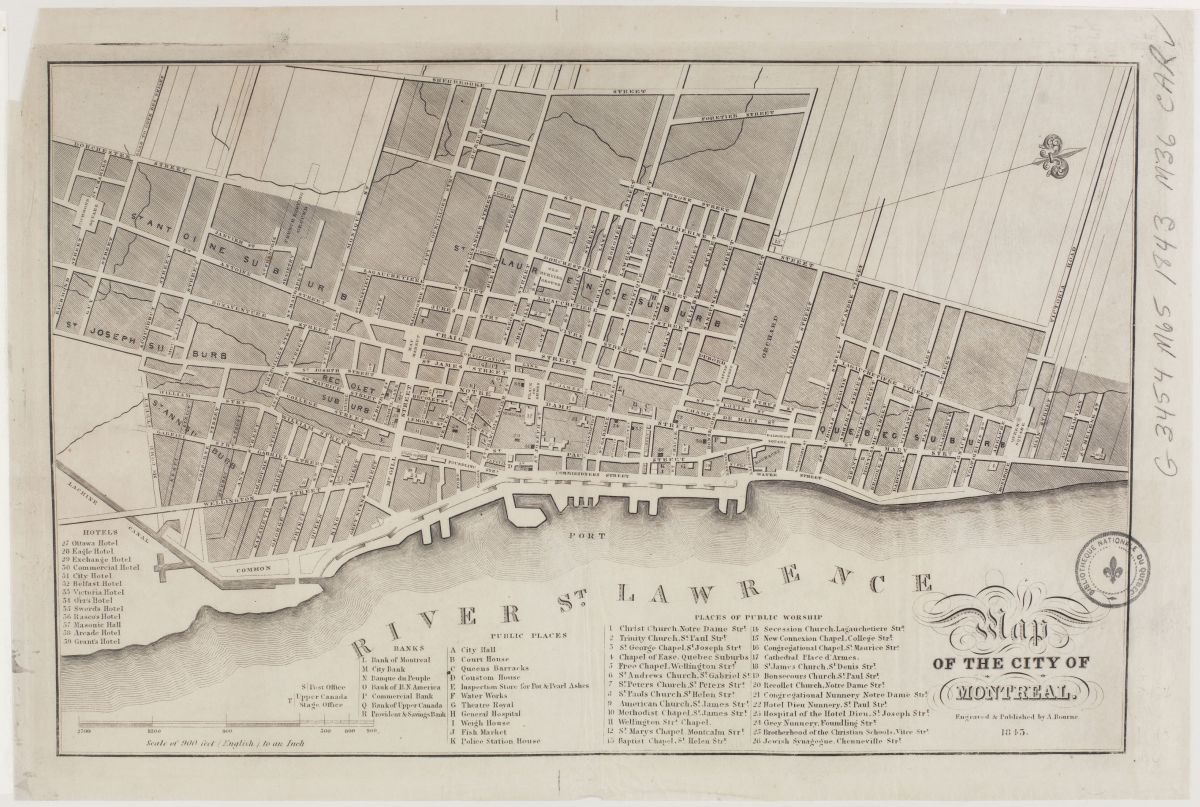

The Neighbourhood

The William Wragg family lived and worked in what is now Old Montreal, close to the harbour. With Margaret’s help, I have been able to orient myself and discover where William Wragg’s home and business was. A sale of land in 1835 for a property next to Wragg’s gives the information I needed (emphasis mine):

A lot or emplacement situated and being in the city of Montreal, containing eighty feet in front by fifty six feet in depth, the whole more or less, bounded in front by St. Paul street, in rear by Louis M. Viger, esquire, on one side to the north east by the representatives of the late William Wragg, and on the other side to the south west by Dominique Mondelét, esquire, with one three story stone house, the first story of which is of cut stone, divided into two tenements, (fire proof) one new four story cut stone house, covered with tin, one four story cut stone store, sixty four feet long, with ice house, stables, &e. the wall which separates the yard of the lot above described from the yard of the house of the said Dominique Mondelet, esquire, as also the stable of the house which divides the said lot from that of the said representatives of the late William Wragg are mitoyens [adjoining].[xxii]

The Quebec Gazette, Vol. XII, No. 32, 11 Jun 1835, p. 2.

The 1819 Montreal Directory shows that Louis M. Viger, Advocat, lived at 1 Bonsecours. He owned what is now the historically designated “Pierre Calvet House” at the corner of Bonsecours and St-Paul and was a very influential man in Quebec Patriote politics.[xxiii] It is also interesting to note that in addition to Louis-Michel Viger, an ardent Patriote, another patriote and Viger’s cousin, Louis-Joseph Papineau lived at 5 Bonsecours. From various cited connections, the Wraggs were likely Tories, so tensions between Wragg and some of his neighbours may have existed.

Directly across the street from this location is Notre Dame Bonsecours Chapel which dates to 1771 although its exterior is now different from what it would have been in the early part of the nineteenth century. It was originally built as a place of pilgrimage on the site of the first stone chapel.[xxv]

Today the Bonsecours Market stands beside the Chapel, but it was not there when William Wragg lived at 12 St-Paul. John Molson bought the property in 1815 and built a pier at that location. He also expanded the house then standing on the property in order to transform it into a hotel which was known under several different names. The first hotel was destroyed by fire, then rebuilt in 1825 as the British American Hotel. This building burned down in 1833. [xxvii]

Molson also financed the building of the Royal Theatre on the southwest corner of his St-Paul property. He sold shares at ₤25 each to investors and was himself the largest shareholder. The second largest shareholder was Elizabeth Mittleberger, Widow George Platt. She invested ₤500 for 20 shares. William Wragg appears to have purchased one share.[xxix] Here again, we see a divide between the English and French communities. Of the 90 subscribers only 7 had names which were of French Canadian origin. The theatre was a 1,000 seat Georgian-style playhouse and it opened to the public on November 21, 1825. The local papers reviewed the evening as a success with the first play being Reynold’s comedy of the “Dramatist Or, Stop Him Who Can![xxx] The theatre was demolished in 1844 when John Molson’s son sold the property to the City of Montreal. Construction began on the new Bonsecours Market which was completed and inaugurated in 1847.[xxxi]

The first Notre Dame Church, located beside Place D’Armes, was built between 1672 and 1683. By the 1800s the church was too small for the growing congregation and plans were made for a much larger building. Construction began in 1824 and the new church was consecrated on July 15, 1829. It was declared a minor basilica in 1982.[xxxii]

Postscript

I don’t believe that William Wragg’s house and outbuildings remain on St-Paul. Very few buildings that pre-date the Victorian era have survived. William’s buildings were probably set back from the street some distance as his closest neighbour describes his property as being to the “north east”. In 1821 William was renting out the first two floors of his house: “To Let, Two flats of the subscriber’s house, No 12 St Paul Street. The lower flat would answer well for a Grocery Store, and the upper for a private family.”[xxxiv] In addition to his house, he would have needed sufficient land for a stable, horses, carriages, blacksmith shop, and forge.

By the 1960s the Port district of Old Montreal had fallen into decay. Once the centre for industry and finance, it was now reduced to a slum. Plans were made to raze the buildings and run part of the proposed Ville-Marie Expressway along the riverfront. Happily this did not happen, although quite a few old neighbourhoods were bulldozed to make way for the Expressway in the 1970s.[xxxv] In 1964, the Government of Quebec and City of Montreal declared “Old Montreal” to be an historic district and this was accompanied by an amendment in 1963 to the Historic Monuments Act.[xxxvi] Considerable expense and work then began to enhance the district which is now a major historic and tourist attraction.

[i] Sproule, Robert Auchmuty (1799-1845), watercolour on paper “The Port of Montreal, 1830”, gift of David Ross McCord, McCord Collection, Object M303, in the Public Domain (Source: collections.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/en/objects/11412/the-port-of-montreal-1830: accessed 18 May 2022).

[ii] After Richard Jr, Juliann and Nancy were apprenticed in 1819, it appears that Richard Sr, his second son, John Darling Graves, and, by inference, his wife Juliann moved to Quebec City where Richard, together with his brothers John and William, took on a work project at Cap-Santé on the Rivière Portneuf. If still living, their son Thomas, aged ten would have been too young to be apprenticed to a trade and daughter Mary, aged four, was simply too young to be parted from her mother. I have found no further records relating to Juliann Maville or to Thomas or Mary Graves.

[iii] “An Alphabetical list of the merchants, traders, and housekeepers, residing in Montreal [1819]” (Source: Ancestry.com: accessed 14 May 2022). Note that Ann Wragg Platt was apparently renting out lodging as she is designated with the letters “HK” for “housekeeper”.

[iv] Bourne, Adolphus (1795-1886) “Map of the City of Montreal” 1843, engraved & published by A. Bourne, 1843, from the Collection Saint-Sulpice (Cartes et plans), in the Public Domain (Source: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec [BanQ], https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2243939: accessed 18 May 2022).

[v] Beek, John Gerbrand, Notariat, Apprenticeship Contract for Richard Graves, Acte 2346 dated 21 Aug 1819, Actes de notaires, 1781-1822, Montréal, Quebec (Boîtes 15-21, 20 déc 1800-28 mai 1822, BanQ), (Source: FamilySearch, Film #1420238, DGS #8321643, Images 3071-3073: http://www.familysearch.org: accessed and transcribed by Bette Smith 23 Aug 2021).

[vi] Beek, Apprenticeship Contract for Juliann Graves, Acte 2347 dated 21 Aug 1819, Ibid. (Images 3074-3076: accessed 23 Aug 2021).

[vii] Beek, Apprenticeship Contract for Nancy Graves, Acte 2348 dated 21 Aug 1819, Ibid. (Images 3077-3079: accessed and transcribed by Bette Smith 22 Aug 2021).

[viii] Lacelle, Claudette, “Domestic Servants in 19th-Century Canada” (translated from the Original French), Studies in Archaeology Architecture and History (Ottawa: Environment Canada-Parks, 1987), pp. 15-16, 33 (Source: http://www.parkscanadahistory.com/series/saah/urbanservants.pdf: accessed 17 Jun 2022).

[ix] Ibid., pp. 39-40.

[x] “Apple Dumplings – from the Painting by G.D. Leslie” illustration, Canadian Illustrated News, Vol. 25, No. 18, 6 May 1882, p. 281 (https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06230_651/2: accessed 17 Jun 2022).

[xi] Lacelle, Ibid., Appendix E, p. 156, citing original source : Guiral, Pierre and Thuillier, Guy, La vie quotidienne des domestiques en France au XIXe siècle (Paris: Hachette, 1978), pp. 79-80 (translation).

[xii] Quebec Family History Society, Montreal’s Early Cemeteries, St Lawrence Protestant Burial Ground, 1799-1854 (Old Protestant Cemetery), Register 1, 1822, p. 414, Digital Image 0598.

[xiii] Ingrid Peretz, “Whose Bones are These?: Montreal’s mystery of an unknown soldier and abandoned graves” Globe and Mail, 24 Jul 2017 (Source: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/montreal-cemetery-mystery/article35779860/: accessed 12 Dec 2018).

[xiv] Panet, Louis, Notariat, Apprenticeship Contract for John Darling Graves, Acte 401 dated 18 Feb 1822, Actes de Notaires, 1819-1879, Quebec, Quebec, (Boîtes 1-5, no. 1-548, 4 nov 1819-16 août 1822, BanQ), (Source: FamilySearch, Film #2242864, DGS 8885432, Images 6276-6279, www.familysearch.org: accessed 27 Jun 2022).

[xv] Panet, Louis, Notariat, Power of Attorney, Acte 917 dated 21 Nov 1823,Actes de Notaires, 1819-1879, Quebec, Quebec, (Boîtes 5-9, no. 549-1225, 16 août 1822-30 oct 1824, BanQ), (Source: FamilySearch, Film #2242865, DGS 8885433, Images 4327-4330, http://www.familysearch.org: accessed 27 Jun 2022).

[xvi] 1825 Census of Lower Canada (Quebec), Montreal District, Montreal (Town) Sub-District, p. 72, 2095,William Wragg (Source: Library and Archives Canada [LAC], Ottawa, online digital image Item 33832, https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item/?app=Census1825&op=img&id=004569588_00606: accessed 18 May 2022).

[xvii] I had thought the second girl might have been William and Sophia’s daughter Amelia Sophia. However, the 1825 census was taken between 20 Jun and 20 Sep 1825. Amelia’s baptismal entry states that she was born 27 Nov 1826.

[xviii] Doucet, Nicolas-Benjamin, Notariat, Apprenticeship Contract for Benjamin Wragg Jr., Acte 9505 dated 25 Feb 1822, Actes de Notaires, Montréal, Québec, (Boîtes 56-61, no. 8680-9668, 1 may 1821-20 avr 1822, BanQ), (Source: FamilySearch, Film #1452243, DGS #8864645, Images 4658-4661, http://www.familysearch.org: accessed 25 Jun 2022).

[xix] 1855 New York US State Census, Cayuga County, Auburn, Ward 4, Dwelling 91, Family 108, Benjamin Ragg [sic] (Source: Ancestry.com, New York, US, State Census, 1855 database on line, Image 36: accessed 27 Jun 2022).

[xx] “Montreal 31 juillet”, Le Canadien, Quebec, Quebec, Vol 5, No. 29, Wed, 4 Aug 1824, p. 1 (Source: BanQ, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3453812: accessed 23 Jun 2022).

[xxi] “Notice”, The Montreal Herald, Wed. 13 Feb 1828, Vol. XVII, No. 30, p. 2 (Source: BanQ, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3112687: accessed 24 Jun 2022).

[xxii] “Sheriffs Sales District of Montreal, Fieri Facias…No. 333”, The Quebec Gazette, Vol. XII, No. 32, Thu. 11 Jun 1835, p. 2 (Source: BanQ, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4370279?docpos=2: accessed 27 Jun 2022).

[xxiii] de Lorimier, Michel, “Viger, Louis-Michel,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003 (Source: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/viger_louis_michel_8E.html: accessed 23 June 2022).

[xxiv] Photograph, Maison Pierre Calvet (Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maison_Du_Calvet_12.jpg.

Jeangagnon, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons: accessed 28 Jun 2022).

[xxv] “A historical and Heritage Gem” Historic Site—Marguerite Bourgeoys—Head Back through Time (https://margueritebourgeoys.org/en/history/: accessed 25 Jun 2022).

[xxvi] Walker, John Henry (1831-1899) Wood engraving “Notre Dame de Bonsecours Church, Montreal” gift of David Ross McCord, McCord Collection, Object M930.50.8.243, in the Public Domain (Source: collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en/objects/21752/notre-dame-de-bonsecours-church-montreal: accessed 18 May 2022).

[xxvii] The Bonsecours Market and Montreal: From One Era to the Next” (marchesbonsecours.qc.ca/en/historique.html: accessed 26 Jun 2022).

[xxviii] Smith, Pemberton, A Research into early Canadian masonry, 1759-1869 (Montreal: Quality Press Ltd., 1939, Frontispiece depicting the “British American Hotel”), (Source: BanQ, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3259528?docpos=5: accessed 27 Jun 2022).

[xxix] Griffin, Henry, Notariat, Articles of Agreement … for Establishing a Theatre in Montreal by Joint Stock, Acte 5547 dated 1 Feb 1825, Actes de notaires, 1812-1847, Montréal, Quebec (Boîtes 25-28, no. 4842-5574, 2 août 1823-16 févr 1825, BanQ), (Source: FamilySearch, Film #1570375, DGS #8328690, Images 6497-6514: http://www.familysearch.org: accessed 28 Jun 2022).

[xxx] Klein, A. Owen, The Opening of Montreal’s Theatre Royal, 1825” Theatre Research in Canada/Rechereches Théâtre au Canada, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring 1980): 24-38, (htps//journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/TRIC/article/view/7539/8598: accessed 26 Jun 2022).

[xxxi] “The Bonsecours Market and Montreal: From One Era to the Next”, Ibid.

[xxxii] Sabourin, Diane, “Notre Dame Basilica of Montreal” The Canadian Encyclopedia (published online 25 Nov 2012 and updated by Maude-emmanuelle Lambert, 12 Apr 2017, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/notre-dame-basilica-montreal: accessed 26 Jun 2022)

[xxxiii] Sproule, Robert Auchmuty (1799-1845), watercolour, graphite & ink on paper “The Place d’Armes, Montreal, 1828”, gift of David Ross McCord, McCord Collection, Object M385, in the Public Domain (Source: https://collections.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/en/objects/12311/the-place-darmes-montreal-qc-1828)

[xxxiv] “To Let”, The Montreal Herald, 21 Sat., 17 Feb 1821, p. 1 (Source: BanQ, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3112661: accessed 26 Jun 2022)

[xxxv] “4.4 Ville-Marie Expressway”, Montreal Master Plan, November 2004, p 222. (http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/pls/portal/docs/page/plan_urbanisme_en/media/documents/041123_4_4_en.pdf: accessed 26 Jun 2022). “General Goals: Optimize the development of the area in order to restore links between Old Montréal and Faubourg Saint-Laurent, Improve the image of the area and allow for a more pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly environment.” Part of the Plan would include covering over the former Expressway in this area.

[xxxvi] “The Government of Quebec and the City of Montreal celebrate the 50th anniversary of Montreal’s heritage site, Old Montreal”, published online 12 Sep 2014 (http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=5798,42657625&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL&id=23598: accessed 27 Jun 2022).

What a wild ride! I can only imagine the very difficult decisions our forebears faced, and the illustrations were beautiful also…

LikeLike

This makes our ancestors come alive as real, living and breathing people!

LikeLike