Bette Smith>Mildred Cameron>Stella Knox>Wm Wallace Knox>Margaret Anderson>Ann Graves>Richard Darling Graves>Mary Wragg>Richard Wragg (my 6th great-grandfather)

Research Findings

Last year, my sister Dorothy and I commissioned a professional historical and legal researcher, Susan T. Moore, to find the original records related to Richard Wragg’s incarceration and trial on the charge of High Treason for counterfeiting Guineas. Ms Moore works extensively with National Archives records and has written a book on researching the Equity Courts. While she had not previously researched Royal Mint records, we were confident she would be able to find any records of the trial which would be housed in the Royal Mint folios, including regional court records (Assizes). Susan Moore’s final report[iii] on Richard Wragg included the following folio excerpts:

ASSI 44/76

Assizes: Northern Circuit

Indictment files 1761

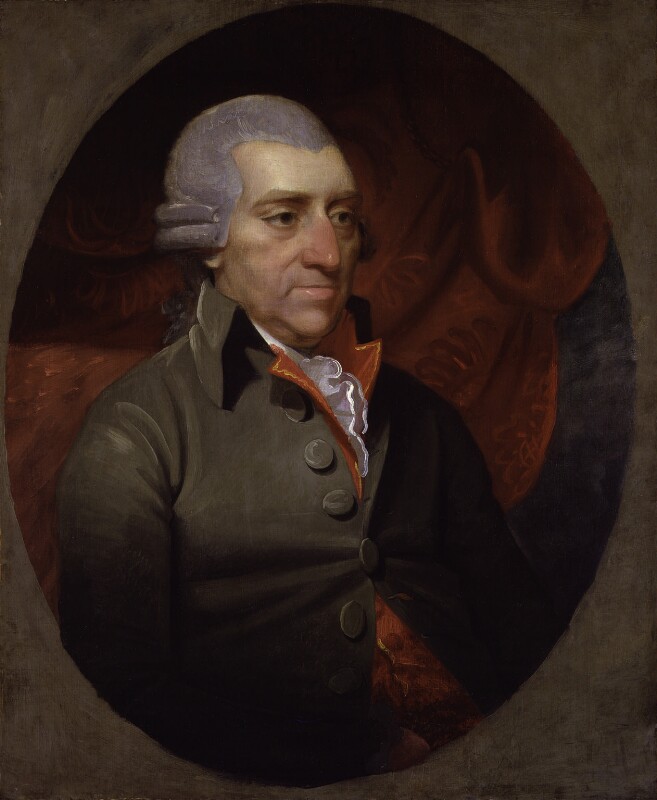

A Calendar of Felons and other malefactors now confined in His Majesty’s Gaol of the Castle of York for what, when and by whom committee in order to take their trials at the Assizes to be holden for the county of York on Saturday 7th March 1761. Before the Rt Hon William Lord Mansfield Lord Chief Justice of his Majesty’s Court of Kings Bench [emphasis Bette’s] and the Honourable Sir Sydney Stafford Smythe knight one of the Barons of his Majesty’s Court of Exchequer

Prisoners names

Richard Wragg a bill of indictment being found against him at [t]he last assizes for high Treason, order to remain in Gaol until the next Assizes. Signed: John Close clerk of Assize

Folio 158

Wiltshire Spring Assizes [not clear if this is really so, but it is the last heading a couple of pages before the following entry]

The account of Wm Chamberlayne solicitor to the mint for prosecuting of coiners and of the gold and silver coin from Christmas 1759 to Christmas 1760

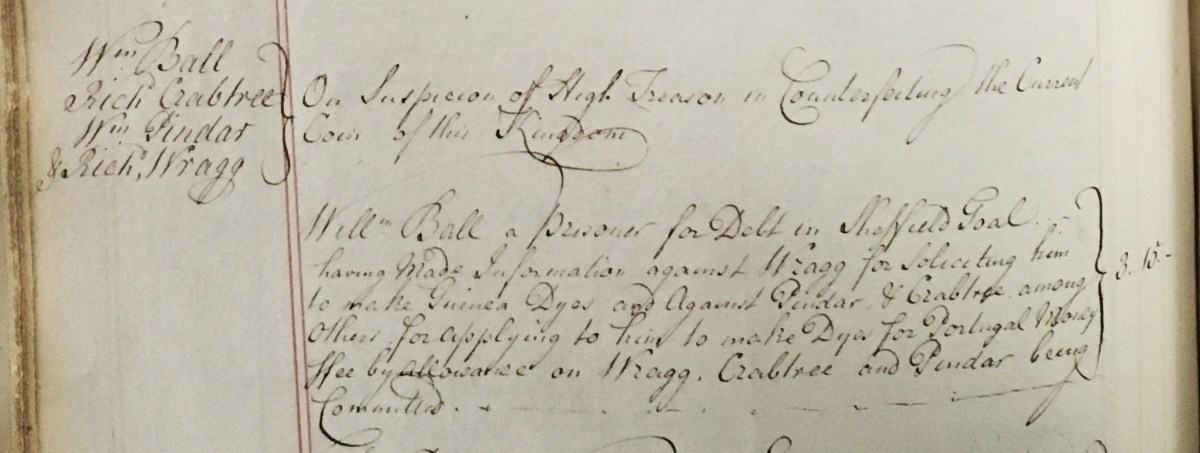

William Ball, Richard Crabtree, Wm Pindar and Richard Wragg

On suspicion of High Treason in Counterfeiting the current coin of this kingdom

Wm Ball a prisoner for debt in Sheffield Gaol having made information against Wragg for soliciting him to make Guinea Dyes and against Pindar and Crabtree among others for applying to him to make dyes for Portugal money

Fee by allowance on Wragg, Crabtree and Pindar being committed: £3 15s

Folio 163 and 164

York Spring Assizes 1761

Richard Wragg, Richard Crabtree, Wm Pindar

The former for High Treason in having Guinea moulds in his custody without lawful authority or sufficient excuse, the other two for conspiring to coin Portugal money

Wragg was acquitted contrary to the opinion of the Judge who told the jury he hoped they would not hereafter complain if they received bad money. Crabtree and Pindar traversed their indictments until the next assizes

ASSI 41/4

Gaol Book 1736-1762

Searched York Assizes spring and summer 1761

Gaol Delivery 7th March 1761

Richard Wragg, Thomas Hill, Henry tile, Ann Bateman, Zecheriah Tiplady, Thomas Banks: Not guilty. To be discharged

Imprisonment at York Castle

At the time of Richard’s indictment, accused persons had no lawyers to speak on their behalf at their trial. The prosecutors presented their evidence, the accused spoke on their own behalf and possibly presented character witnesses, and a jury of twelve men (all of whom had to be landowners) would bring in a verdict of guilty or not guilty. I think Richard must have had the gift of the gab as he was found not guilty, even though he was caught in possession of counterfeiting tools. All three men were fortunate in their verdicts, as a sentence of death could have easily been given. In the case of counterfeiting currency, men found guilty were to be hanged while women were to be burned to death at the stake. The last execution for counterfeiting was carried out in 1827.[vii]

Richard Wragg was imprisoned in York Castle from May 1760 to the beginning of March 1761, a period of ten months. John Marsh in his book Clip a Bright Guinea provides background information on living conditions within the prison in the 1700s. The building was completed in 1705 and was described by Daniel Defoe as “the most stately and complete of any in the whole kingdom, if not in Europe”. John Wesley visited the prison in 1759 and “supposed that the prisoners were well off, although they were crowded in a large but insanitary building.” Criminals, either awaiting trial or convicted, were kept on the ground floor and debtors had better accommodation on the top floor. Men and women were housed separately.[viii]

Positive opinions of the time were offset by that of John Howard, the 18th century prison reformer, who described it circa 1770 as “a noisome place with cells that were little more than unlighted dungeons, and, thanks to those who inhabited them, filthy and fever-haunted dens of inquity in which hundreds of people in festering masses were confined”.[ix]

Marsh goes on to describe the day-to-day conditions for the prisoners under the Chief Gaoler, William Clayton (who shows up on the accounting records pertaining to Richard’s incarceration).

Marsh writes:

Every Tuesday and Friday the prisoners were each allowed a 6d. loaf which weighed 3 pounds 2 ounces. For the rest, they relied on relatives and friends and any charitable minded soul to bring them food and drink….

The cells [for felons] were small and had no water, being but 7 ½ feet by 6 ½ feet. They were 8 ½ feet high. The day room for men was only 24 feet by 8 feet and frequently held scores of men at any time. In most of the cells were three prisoners. In winter the doors remained locked for upwards of sixteen hours each day. There was straw on the floors and no bedsteads. An open sewer running through the passages made this part of the prison offensive in the extreme…..

when exercising in the courtyard, the prisoners were able to confer with their friends outside.[x]

While Richard Wragg was released from prison on March 7, 1761, his two co-accused, Richard Crabtree and William Pindar, were held over to the summer assizes. Susan Moore reported on the outcome[xi]:

Assizes 11th July 1761 – Northern Circuit 41/4

Richard Crabtree. Guilty misdemeanour to be imprisoned 6 months till he pay a fine of £100 and also until he give security with two sufficient sureties for his good behaviour for 12 months himself in £200 and his sureties in £50 each

William Pindar the younger. Guilty misdemeanour to be imprisoned 3 months till he pay a fine of £40 and also until he give security with two sufficient sureties for his good behaviour for 3 months himself in £200 and his sureties in £40 each

Prison Reform

Richard’s ten-month incarceration would have been a squalid and miserable experience. Prison reform really only began with the work of John Howard who had toured prisons in both England and Europe during his lifetime, including York Castle likely in the 1770s. He presented evidence on his findings to a British House of Commons committee in 1774 which led to the Penitentiary Act of 1779. “He advocated a system of state-controlled prisons in which the regime was tough, but the environment healthy.” As well, he believed prisons should be used to reform and rehabilitate prisoners rather than simply to punish them. Although the plans set out in the 1779 Penitentiary Act were not carried out, it did begin an interest in prison reform that continued well after Howard’s death in 1790.[xii]

Out of the Frying Pan

Richard Wragg married Mary Darling on July 17, 1758, three months pror to the baptism of their eldest child Ann. Their second child, my fifth great-grandmother Mary, was baptized in Ecclesfield on December 7, 1760 while Richard was incarcerated in York Castle. Their third child, Sarah, was baptized July 3, 1763 in Ecclesfield. Richard and Mary Wragg remained in Yorkshire for several more years. In 1768 or 1769, the Wragg family immigrated to Saratoga, New York, just in time for the American Revolution.

[i] “Keep in mind those who are in prison, as though you were in prison with them; and those who are being badly treated, since you too are in the body” Hebrews 13:3

[ii] W Lindley, etching,York Castle Prison, 1759. Image in the Public Domain provided courtesy of York Museums Trust. (https://yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk/ accessed 26 Mar 2023). By the time this image was made, the prison had become a tourist attraction. Note the gentry as they walk past the prison could view the prisoners standing in the railed courtyard (centre back of etching).

[iii] Susan T. Moore, MA, “Smith Mint 2022 Jan V03” Report, prepared for Bette Smith and Dorothy J. Smith, 17 Feb 2022. Digital documents held by Bette Smith, Kitchener ON and Dorothy J. Smith, Ottawa ON.

[iv] John Singleton Copley, “William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield”, oil on canvas, exhibited 1783, Ref NPG 172, © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used under Creative Commons License issued 27 Mar 2023. (https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp02942/william-murray-1st-earl-of-mansfield ; accessed 27 Mar 2023)

[v] Westminster Abbey, Commemorations, “William Murray, Lord Mansfield”: “Holding many high ranking judicial posts he was Lord Chief Justice of England from 1756-88. He played a key role in ending slavery in England with his judgment in the case of James Somerset. In 1776 he was created Earl of Mansfield.” He is buried in Westminster Abbey. (https://www.westminster-abbey.org/abbey-commemorations/commemorations/william-murray-lord-mansfield ; accessed 25 Mar 2023)

[vi] Moore, “Smith Mint 2022 Jan V03” Report, 1, Image 1450, citing Mint 1/11, Folio 158, Wiltshire Spring Assizes.

[vii] The Royal Mint, “Clippers and Counterfeiters: Notes for Teachers”. (https://www.royalmint.com/globalassets/the-royal-mint/pdf/clippers-and-counterfeiters-notes-for-teachers.pdf ; accessed 25 Mar 2023) and The Royal Mint, “Counterfeits and Cautionary Tales”. (https://www.royalmintmuseum.org.uk/journal/curators-corner/counterfeits-and-cautionary-tales/ ; accessed 25 Mar 2023)

[viii] History of York, “One Thousand Years of Justice at York Castle”. (http://www.historyofyork.org.uk/themes/1000-years-of-justice-at-york-castle ; accessed 26 Mar 2023)

[ix] John Marsh, Clip a Bright Guinea (Otley: Smith Settle Ltd, 2nd ed., 1990), 73. [A personal aside: Many thanks to my sister Margaret for gifting me this book on my recent birthday!] Marsh tells the history of a ruthless gang, the Yorkshire Coiners, led by ‘King’ David Hartley in the late 1760s. It was their criminal activities that forced the government to finally withdraw the old currency and replace it with coins having milled edges. Following the gang’s murder of William Deighton, a Halifax excise man, in 1769, gang members were arrested. Their leader, David Hartley was convicted of “clipping and diminishing the Gold Coin” and was hanged at Tyburn, near York on April 28, 1770. The gang’s activities did not end, however, until the next decade.

[x] Marsh, 73-75.

[xi] Moore, “Smith Mint 2022 Jan V03” Report, 4.

[xii] UK Parliament, “John Howard and Prison Reform”. (https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/laworder/policeprisons/overview/prisonreform ; accessed 26 Mar 2023)

[xiii]James Gillray, (John Howard) “The Triumph of Benevolence” stipple and line engraving, published 21 Apr 1788 by Robert Wilkinson, Ref NPG D12059 © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used under Creative Commons License issued 26 Mar 2023. (https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw63352/John-Howard-The-triumph-of-benevolence?LinkID=mp02293&role=sit&rNo=2 ; accessed 26 Mar 2023)

[xiv] Mather Brown, “John Howard”, oil on canvas, feigned oval, circa 1789, Ref NPG 97, © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used under Creative Commons License issued 26 Mar 2023. (https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw03271/John-Howard?LinkID=mp02293&role=sit&rNo=0 ; accessed 26 Mar 2023)

Interesting post! The title of Clip a Bright Guinea reminds me that related charges could be laid for clipping, shaving, or filing genuine coins. They may have been the source of the metal meant to be poured into those moulds. Also, characterful aside from the judge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, Ed. Yorkshire was a hotbed of clipping for decades before the government decided to act. Marsh’s book definitely states that the clipped metal would be used to produce new coins, while the clipped coin became further and further debased, sometimes by as much as 20%. Gang members would pick certain persons and suggest they loan a few coins “for attention” before returning the now clipped coin to the owner. People seldom refused.

LikeLike

What an interesting story! Now we have to wait, I suppose, to find out what happened to the Wragg family next!

Margaret Smith Goldik

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, but that is already in our wonderful book! More prison, this time as a political prisoner. Damn Yankees!

LikeLike

Betsy!!! He is my 6th great grand as well!!!

LikeLike

Very well researched and written! Love the details; they really make those days come alive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks and thanks too for giving this a helpful proof-read prior to publishing.

LikeLike

Betsy, a freind just gave me a listing of loyalist from Saratoga and I just took a name and googled. Imagine my surprise. So what else do you have? Do you want to send me a note historiantosaratoga@gmail.com I would love to hear more and plan some appropriate recognitions as we enter into the 250th of the AWI. (I am currently at a conference focused on the 250th.)

LikeLike