Bette Smith˃Mildred Cameron˃Harvey Cameron˃Ellen McMillan˃Hugh McMillan & Ellen McLean

Post-Napoleonic War Britain

In 1818, Hugh McMillan, aged 33 years, and Ellen McLean, 27 years, were newlyweds living in the Gorbals, a poor Glasgow neighbourhood. Hugh was a weaver, but whether he was employed at that time is unknown. Their daughter Christine was born September 11, 1819. To say that Hugh’s young family was living in a time of great unrest is an understatement. Much had changed since the end of the Napoleonic Wars and not for the better.

There was a brief spirit of jubilee in Britain following the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo on June 18, 1815. The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars had been raging for 23 years and only ended with Napoleon’s abdication on June 22nd. Peace had arrived at last.

Peace, however, came with a price. An economic slump affected Europe, Britain and North America and Britain was left with a staggering war debt. It had increased from ₤232 million (circa 117 per cent of GDP) at the time of the American Revolutionary War to ₤834 million (circa 250% of GDP) at the time of the Battle of Waterloo.[i]

At the same time, approximately 350,000 soldiers were released from the army and returned home in search of jobs. Wealthy landowners, fearing a loss in agricultural revenue due to imported grain, used their influence to impose protectionist tariffs. The resulting Corn Laws of 1815 dramatically drove up the cost of bread and manufacturing while the economy stagnated.[ii]

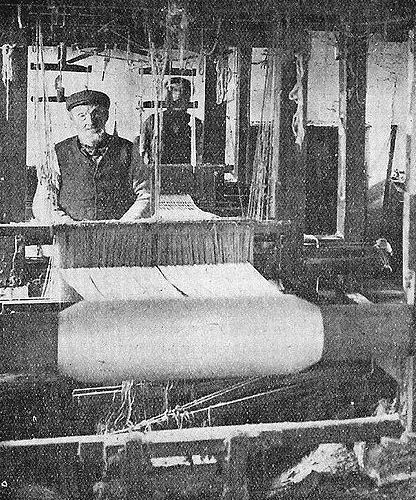

Industrialization, primarily in the textile industry, also played a role in the economic slump. Mechanized looms replaced adult male weavers with cheaper labour provided by women and children.

They [the handloom weavers] are the best known example, but by no means the only one. They starved progressively [sic] in a vain attempt to compete with the new machines by working more and more cheaply. Their numbers had doubled between 1788 and 1814 and their wages risen markedly until the middle of the Wars; but between 1805 and 1833 they fell from 23 shillings a week to 6s, 3d.[iv]

In response, the weavers of England and Scotland protested, going on strike for various periods of time, as they unsuccessfully agitated for job protection and wage increases.

In a country where just two per cent of the population held the vote, political activists were calling for universal male suffrage to give working and middle-class men a say in government. The ruling landed class—that two per cent who held the vote—were frightened by the radical rhetoric and the call for government reform. No doubt they were remembering the toppling of Royalists in both the French and American Revolutions. The overwhelming response by the government they controlled was to repress any hint of dissent.

Manchester, Lancashire—“The Peterloo Massacre”

On April 16, 1819, a crowd of 60,000 people, mostly weavers, but including women and children dressed in their Sunday best, assembled in St. Peter’s Field, Manchester. They were there to listen to several radical speakers, including popular orator Henry Hunt. The speakers called for the vote to be extended to the poor and for government reform. Local magistrates, fearing violence, read the Riot Act calling for the crowd to disperse.

Since few people could hear that the Riot Act had been read, the crowd remained. That was the signal to send in armed cavalry troops who were to arrest the speakers and disperse the crowd. Yeoman cavalry, followed by the 15th Hussars, charged the crowd, slashing with their sabres and trampling people beneath the hooves of the horses.

In the end, eighteen people, including a two-year-old boy, were dead and hundreds were severely injured by sabre wounds or trampling.[vi] A journalist for The Times was present on that day and his eye-witness account can be read in a recent article from The Times which includes stills from the 2018 film Peterloo.[vii]

A short featurette (4.43 min) on the making of the film Peterloo is fascinating in its behind-the-scenes look at the characters and roles as portrayed in this event. It’s available to view at https://youtu.be/_HQo5iVL3pw?feature=shared. A trailer for the film itself can be viewed at https://youtu.be/t1Wp37haiG4?feature=shared (1:28 minutes).

Bonnymuir, Stirlingshire—The Radical Rising of 1820

Unrest was also growing in Scotland. Over decades, highland landowners had evicted their tenant farmers and enclosed their fields for grazing sheep. Many of these highland tenant farmers, including our ancestor Hugh McMillan, migrated to Glasgow where they became weavers. Since the war ended, many were unemployed and those who were employed still could not support their families on what they earned.

The ripples caused by the Peterloo Massacre were felt in Scotland, most keenly among the Glasgow weavers. Working-class folk began to agitate for universal male franchise, annual parliaments and the repeal of the Act of Union of 1707 which had always been unpopular with the people of Scotland.

Thomas Forsythe was a six-year-old child when labour unrest affected his Glasgow family. In later life he wrote “I can remember in the fall and winter of 1819, seeing the rebels, or those they called rebels, marching past our house in great number, mostly after dark.”

Archibald Gardner was also a child when labour unrest troubled his home. Years later he wrote:

Times were poor, business dull, and people became dissatisfied with the government. Meetings were held by agitators, even privately in our own house or tavern. Skirmish after skirmish took place. Although young at the time I still remember the shrill sound of my brother William’s glass bugle when it sounded the turnout call at midnight at the Cross of Kilsythe, two houses from ours. The sound of doors opening and shutting along the street, the bugle call, the din that grew louder as company after company went by, made up a night not soon to be forgotten. In a pitched battle that followed, the radicals were defeated.[viii]

Was Hugh McMillan one of those men who marched the Glasgow streets at night?

Expecting trouble, the government sought to forestall rebellion by planting spies in the radical movement as well as government provocateurs whose actions might smoke out like-minded radicals.

Between 1 and 8 April 1820, across central Scotland, some works stopped, particularly in weaving communities, and radicals attempted to fulfil a call to rise. Several disturbances occurred across the country, perhaps the worst of which was a skirmish at Bonnymuir, Stirlingshire, where a group of about 50 radicals clashed with a patrol of around 30 soldiers.[ix]

Some of the radicals at Bonnymuir were armed with guns but most had only pikes. They were vastly outmatched by a small government force of Hussars and Stirlingshire Yeomanry. They were forced to surrender and were marched to Stirling Castle.[x]

The insurrection was quickly put down and trials were held between July and August 1820. The government issued bills of treason against 88 men involved in the uprising. Many of these had already fled the country. Nineteen of those convicted of treason were transported to Australia. Former soldiers John Baird and Andrew Hardie, two of the ringleaders, were tried at Stirling Castle and were found guilty of High Treason. Each was sentenced to death:

“To be drawn on a Hurdle to the place of Execution and be there Hanged by the Neck until he be Dead and afterwards his Head to be severed from his Body and his Body directed into four quarters be disposed of as our Lord the King shall think fit”. National Records of Scotland, Treason Trials, County of Stirling, JC21/2/1[xi]

Baird and Hardie were executed at Stirling on September 8, 1820. The sentence was commuted (if we can call it that) to hanging and decapitation only. James Wilson, the third ringleader, was tried and executed in Glasgow.

This was to be the last uprising in Scotland.

For an indepth account of “Bonnymuir and the Fate of Baird and Hardie” you can view the video produced by the Scottish History Youtube channel (16.48 minutes) at https://youtu.be/S1-7b-Z4UKw?feature=shared

A Canny Plan

It soon became apparent that it was in the government’s best interest to rid Scotland of its discontented weavers. Lord Archibald Hamilton (MP Lanarkshire) and John Maxwell (MP Renfrewshire) brought petitions to the government in support of employed workers who were unable to feed their families.

Suggestions were made to provide weavers with assisted emigration to Canada. The weavers would have a new start and, at the same time, troublemakers would be kept far from home.

In the winter of 1819 emigration societies began to form, urging government action and raising funds by private subscription. Their petitions “for liberty to emigrate with their families to Upper Canada, and that the Government be graciously pleased to grant one hundred acres of land, free of any charge, along with aid in money, implements of husbandry, and building materials” were presented to Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. By the spring of 1820 Lord Bathurst was writing to Sir Peregrine Maitland, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, advising that 1,000 settlers, who wished to locate near friends and relatives in the area of Perth and the Rideau River, would soon be on their way.[xii]

Farewell to Scotland

There were 45 emigration societies which received government assistance. In two years, about 3,300 emigrants were approved to receive land in Lanark County, Upper Canada. About 1,500 sailed from Glasgow and environs in 1820. The following year, 1,892 emigrants raised the necessary funds to pay their deposits and secure passage.

The 1821 group included our ancestors Hugh McMillan, his wife Ellen McLean, and daughter Christian. The Glasgow Herald published an annoucement of the society settlers’ departure.

Greenock, April 13.—This morning the [?] ship George Canning, Capt. Potter, sailed for Quebec with 489 passengers, chiefly from Glasgow and neighbourhood, consisting of Weavers, Cotton-spinners, Joiners, Farmers, and Labourers, from the various emigratory associations which the distress of the times has lately called into operation. Of the above number we find there are of males 264—females [?] the adult portion of both is 239—the number of families of which the whole consist, 113. Most heartily do we wish them a speedy passage, and that they may not fail to attain, by their honest endeavours the prosperity they are in quest of.[xiv]

To be continued….

[i] Duncan Needham, “A very short history of the national debt”, p. 11, Centre for Financial History, Pdf Occasional Paper, 2019 (centreforfinancialhistory.org ; accessed 15 Jul 2024).

[ii] The Editors of Encylopaedia Britannica, “Corn Law—British History” (https://www.britannica.com/event/Corn-Law-British-history ; accessed 07 Dec 2024). The Corn Laws were not repealed until 1846.

[iii] Alexander (Sandy) Ogilvie (1791-1871) at his loom in his shop in Land Street, Keith, Moray, Scotland. Scan of 1860s photo on page 29 of the booklet “Recollections of Keith” published in the 1920s. Duncanogi (talk) 18:02, 28 July 2009 (UTC) (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alexander_(Sandy)_Ogilvie_1791-1871,_at_his_loom_in_Keith.jpg ; accessed 07 Dec 2024).

[iv] E.J. Hobdbawm, Industry and Empire: From 1750 to the Present Day, The Pelican Economic History of Britain, Volume 3 (Great Britain: Pelican Books, 1968, reprinted 1981, The Chaucer Press), p. 93.

[v] Richard Carlile (1790-1843), coloured engraving “Peterloo Massacre”,1 Oct 1819, in public domain (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peterloo_Massacre.png ; accessed 07 Dec 2024).

[vi] The Peterloo Memorial Campaign, “The Massacre” (https://www.peterloomassacre.org/history.html ; accessed 15 Jul 2024).

[vii] “The Peterloo Massacre: read The Times eye-witness report”, The Times, promoted content Peterloo, 31 Oct 2018. (https://www.thetimes.com/static/the-peterloo-massacre/?region=global ; accessed 07 Dec 2024).

[viii] Ron W. Shaw, A Swarm of Bees—Lanark Society Settlers 1800-1900, A Journey from Scotland to Upper Canada and Utah (Ottawa: Global Heritage Press, 2018), p. 7.

[ix] Scotland’s People, “The Radical Rising of 1820” (https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/help-and-support/guides/radical-rising-1820 ; accessed 07 Dec 2024).

[x] Josie Campbell, photographer, “Stirling Castle” (copyright Josie Campbell, used under the Wikimedia Commons License https://www.geograph.org.uk/more.php?id=2505314 ; accessed 07 Dec 2024).

[xi] Open book, National Records of Scotland (NRC), “The ‘Radical Rising’ of 1820”, 30 Sep 2020 (Nationalhttps://blog.nrscotland.gov.uk/2020/09/30/the-radical-rising-of-1820/ ; accessed 07 Dec 2024).

[xii] Ron W. Shaw, “The Third Wave: The Lanark Society Settlers”, p. 2 (Excerpt from his 2013 book, A Swarm of Bees, published as an article by the Perth & District Historical Society. Accessed at shaw-third-wave-web.pdf ; 07 Dec 2024).

[xiii] Robert Salmon (1775-ca 1851), painting Ships off Greenock, Scotland, 1813, Cincinnati Art Museum collection, in public domain (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%27Ships_off_Greenock,_Scotland%27_by_Robert_Salmon,_Cincinnati_Art_Museum.JPG ; accessed 07 Dec 2024).

[xiv] The Glasgow Herald, Glasgow, Scotland, Mon Apr 16, 1821, p. 4 (www.newspapers.com ; accessed 07 Dec 2024).

A wonderful job of writing! I can’t wait for the continuation of the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am on tenterhooks! What a great pulling together of the socio-economic threads to tell the story. Awesome work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m impressed, Bette. And I get the feeling th

LikeLike

The entirety of your comment didn’t load. I hope you’ll try again as I would love to hear your thoughts. Bette

LikeLike

Dear Bette:

Interesting! I knew about the Clearances in general, but only regarding the Enclosure Acts.

On a separate note, I was in Beaconsfield this weekend for Margâs concert. A mention of Megâs bruised ribs had me recalling that Dad had a broken rib that never set properly. Is this the case, or am I confusing it with his bad ankle?: which I know definitely exists, as I remember visiting I think Uncle John’s farm and all of us there getting a lift atop the loaded hay-wagon across the highway. When Dad descended – which meant sliding off – he landed hard on that ankle and obviously felt it.

I hope all is well with Dani and yourself, – Edward.

.

>

LikeLike

It’s interesting to me how we do not all remember the same events. Rather like a jigsaw puzzle with everyone working with different pieces. I don’t remember the hay wagon, although I do remember being put on top of either Dick or Pearl. I doubt the horse even knew I was there, but he/she did not move. I checked with Dani. She doesn’t remember Dad having hurt his ribs at any time, although she was aware of his broken ankle.

We’re all well here in KW; we’re going to be getting a prescription supplement for Tiggy who is 13 and appears to be having some stiffness from arthritis. All her tests for more serious ailments came back negative, so osteoarthritis is the likely source for her symptoms.

LikeLike